Education

Within the Carceral System

“Education is not just about going to school and getting a degree. It’s about widening your knowledge and absorbing the truth about life.” – Shakuntala Devi

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” – Nelson Mandela

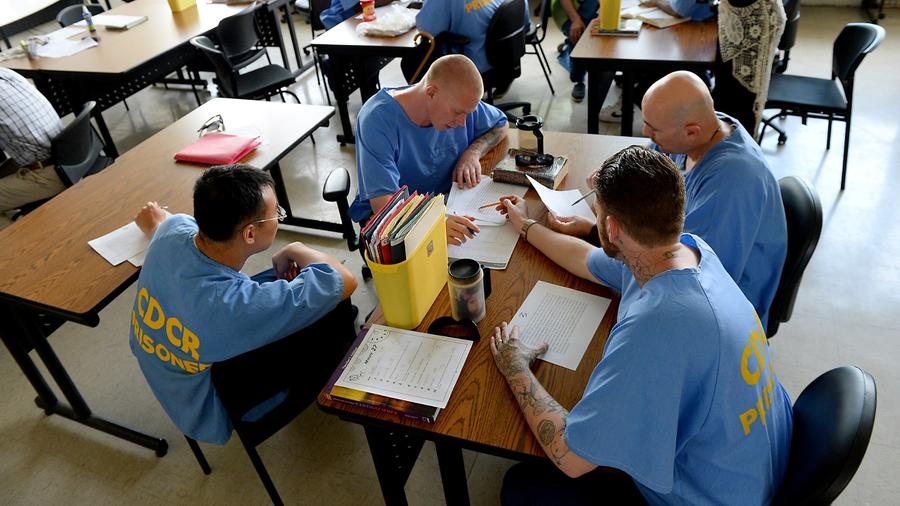

Inmates in Class at the California Rehabilitation Center, Norco CA

A hunger for learning belongs to humans at all stages of life. For those incarcerated, no less than for anyone else, education is essential to finding one’s path forward. Prison education programs come in many forms, and the state of California stands at the forefront of developing them, ranging from individual classes that impart basic practical skills to full degree-granting programs. It is widely recognized today that the use by inmates of educational resources paves the way to increased employment opportunities post-release, and to lower rates of recidivism (return to incarceration).

While rates of incarceration are still tremendously disproportionate towards people of color, California jails and prisons offer more resources and support than do most prisons across the country. This is, paradoxically, in part due to the prison overcrowding problem in the 1990’s which resulted from Governor Reagan’s closure of California mental health institutions, leading to higher incarceration rates and forcing California prisons to accommodate the larger numbers.

Aster Tadesse is an educator who has worked in the field of prison services for over thirty years, with a focus on the opioid addiction crisis that is all too prevalent within the carceral system. She works with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, and she points out that “Rehabilitation” was added only recently to the name of this California institution. She says that 60-70% of people within jails and prisons in California are there due to some relation to drug use, whether it be possession of illegal substances, dealing these substances, or committing a crime while under the influence.

Tadesse began her counseling career in a methadone clinic and then became a “drug education” teacher in Santa Rita Jail. Currently, she teaches at the West County Detention Facility which is a jail in Richmond, and has closely followed the development of education and rehabilitation programs since 1993. The jail’s four step drug education program requires that inmates attend class for three hours every day. The aim is to assist drug or alcohol addiction rehabilitation through learning:

- The first step in the program helps inmates build skills in relapse prevention, including an understanding of the psychological aspect of addiction and the hold that it can have on the mind.

- The second step encourages the building of new relationships with the inmates’ new sober self and with their family and community.

- Step three targets the management of anger, which is often an unavoidable emotion in the carceral experience and also in the process of recovery.

- The fourth step aims to make the inmate’s transition out of jail and back into the community as successful as possible, through short and long term goal setting, as well as assistance from an onsite transition specialist at the facility who helps to connect people with the resources they need to continue their recovery journey, even as they typically return to the same environment where they originally developed an addiction.

This program has been implemented into the majority of California jails and prisons for close to thirty years now, following the pattern of reform that began in the 1990’s. Tadesse wants the public to know that despite all of the valid objections that can be made to the carceral system, this program is something humane happening inside of a jail, and that there are people and programs inside California jails and prisons dedicated to substantially improving the lives of inmates, and not just punishing them. As she ironically puts it: “I tell my students, if you ever want to be in jail, this is the best time for you to be in jail.”

While many prisons and jails in the United States deprive inmates of proper medical care, here again, California is an exception. In the Bay Area’s prison system, including the West County Detention Facility, health care delivery is a priority. “I hate to say this,” comments Tadesse, “but as the students will tell you, they are given more medical follow up in prison and jail than outside.” In the West County Detention Facility, a wide range of services are rendered by medical practitioners, including dentists, eye doctors, and gynecologists for women, as well as general care doctors and nurses. Additionally, Women are sent to hospitals for needs such as childbirth.

The way drug addiction is handled in the West County Detention Facility may hold lessons for treatment in society at large. Every individual first receives a careful medical assessment, with a specific focus on the risk of overdose. Following this, inmates sometimes have the option to join a twelve step program to help with recovery, accompanying Tadesse’s educational rehabilitation program.

Another person who has extensive administrative experience with the programs at the West County Detention Facility in Richmond is Deputy Butler, who has worked for the Contra Costa County Sheriff’s Department for twelve years. He makes sure the jail runs smoothly overall and oversees inmates in their cell blocks, getting them to and from medical appointments and assisting in their interactions with various facilities within the Contra Costa Jail system. As an administrator of a broad range of services in this Richmond jail, Butler draws attention to a new development: the construction of an almost 100 million dollar mental health treatment facility in the jail that will “tackle the custody of inmates with a more holistic approach. It focuses on not just removing people from society, but replanting people back into society.”

Butler says that the biggest change he has seen in the California prison system is the improvement in mental health services. Whereas in the past there was hardly any attention at all given to inmates’ mental health issues, every jail facility now has numerous mental health practitioners who provide counseling and support. Butler says that the vast majority of inmates in the West County Detention Facility –as in most jails and prisons– who are mentally ill have a history of addiction. In carceral environments as in the wider society, drug use has significant psychological causes and consequences.

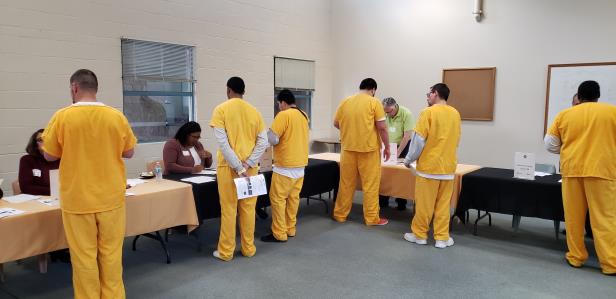

This “holistic” approach in local and statewide California prisons and jails is changing the system. Innovative programs aim to provide prisoners with the tools, mental strength, and resilience they will need in order to re-enter society successfully. Issues such as drug addiction, mental illness, and lack of education have so often gone unaddressed in prisons, although they are the main reasons why inmates end up behind bars again after release.

It is well-known that the way in which those incarcerated and addicted are treated makes all the difference in their recovery. If inmates receive respect and empathy, and have access to resources, including counseling and education, their chances of re-integrating successfully upon release improve enormously. A sure sign of progress being made in local and state California penal institutions is the much improved treatment of staff like Tadesse by the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Educators, Tadesse says, “were begging to teach” three decades ago, but now “they’re begging us to teach” because they recognize how essential educational programs are in jails and prisons.

Butler, and Tadesse both emphasize that the problems of drug addiction and mental illness originate, of course, long before a person sees the walls of a prison or jail. When addressing the roots of addiction, Tadesse emphasizes that “a drug problem is not only a drug problem. It’s a societal problem, it’s a mental problem, it’s a physical problem.” She points out that people use drugs to self-medicate in response to neglect, abuse, depression and shame, to name just a few essential issues. When looking at the links between drug addiction, mental health issues, and the systems that put people in jails and prisons, these facts regarding larger systemic issues have been known for decades, but until recently there has been very little action towards addressing these issues.

Tadesse and Butler are among the administrators and staff who, together with the inmates themselves, grapple daily with the core problems of incarceration and attempt to create a system giving those incarcerated more of a chance to succeed when they leave their cells behind and rejoin the community.